“Travel is glamorous only in retrospect.”

– Paul Theroux

Our small plane took a dive just over the mountain ridge and landed on the narrow field of green. The capable pilot pulled back on the gear and brought the 10-seater in just before it hit the large, worn tire embedded in the earth. It seems that the tire would have been the only thing to save us had the landing gear not worked. Just on the other side of the huge rubber beast was the river, the long opaque brown snake that we had been waiting to explore. The mosquitoes immediately welcomed us as we hoisted our packs from the plane. How is it that the tiny little plane had taken us from the cool, brisk, crowded, insect-free Papua New Guinea highlands and brought us to the hot, sticky, seemingly unpopulated Sepik River Valley in such a short period of time? Stripping off layers, and fumbling in our packs to find repellent, we trudged through the high grass. The local guides lowered our gear down the 8-foot mud wall into the boat that awaited us. With a fair bit of help, thankful for our sturdy hiking boots, we lowered ourselves down the sleek surface, walked over a wood plank into the boat, careful not to fall into the crocodile infested water. The boat took off and the plane and civilization faded into the background. The Sepik expedition had begun.

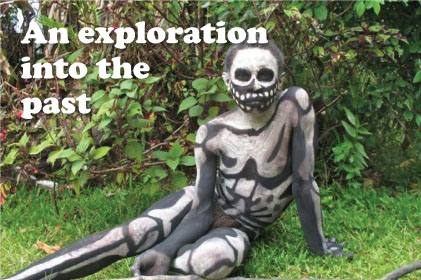

A large portion of our time was spent with primitive groups who were, for the most part, still living as their ancestors had for thousands of years. We found out quickly that these groups are more difficult to find than one may think because tourism and industry have touched almost every corner of our planet. Some of the areas where we did find these removed, primitive groups were deep in the Amazon forest living along the ancient river, high in the Andes mountains of Ecuador and Peru, in remote, rarely traveled areas of China, India and Tibet, and perhaps, most notably, the last uncharted bastion of discovery, Papua New Guinea. These isolated areas were only accessible by foot, long bumpy truck rides, hand-paddled canoes, or single engine planes. With all of the expense and danger associated with getting to and spending time with these tribes, we hoped that the knowledge we would gain would prove beneficial to our research. As it turns out, it has paid off in spades. Not only were the experiences some of the richest and most rewarding of our lives, but by observing so many different tribes in completely different environments, we were able to uncover several universal commonalities in the routines that promoted health in their everyday lives. The first of these similarities was the fact that these remote groups had little or no contact with the outside world. For these people, the tribe or clan was everything. It was the foundation for their happiness, survival, love and spirituality. It bound them, held them, and nourished both their physical and emotional health. Everything that they did, they did for the betterment of that immediate group.

Regardless of these remote tribe's vast geographical differences, we found many similar nutritional practices. Due to the lack of refrigeration and electricity in these regions, their food was always fresh and never processed. They ate only what was available to them through hunting, fishing, farming, foraging, or trading with surrounding tribes. Seasonal eating patterns were also evident in many of the groups. If the tribe lived in an area that experiences a changing of the seasons, it would force a change in their eating patterns due to available food choices. For example, a tribe might plant certain crops along the river and enjoy the fruits of this labor until the river rose, covering their crops and forcing them to live off a diet of almost exclusively fish. While other remote tribes living high in the mountains might get protein from meat once a week at most, and would survive primarily on the carbohydrates they harvest from their crops.

Although the variety of food was extremely limited by American standards, the ingredients were always fresh and natural. Many communities fished daily, while others scavenged for turtle or chicken eggs for their fats and protein. In some communities, such as in the Andes, it was the responsibility of the men to hunt and farm, while on the Sepik River, in Papua New Guinea, it was the sole responsibility of the women to catch enough fish for their families early every morning. Regardless of their cultural and ancestral beliefs and traditions, life depended on daily success in gathering/farming and or hunting/fishing. This meant that physical labor was also a commonality. Life in these remote tribal villages usually involved quite a bit of walking or canoeing from one place to another. It would not be uncommon to see them working or gathering food in this manner for several hours every day.

Most of the health conditions and disease that we observed in these remote tribes were due to insects, poor water sanitation, or day-to-day injuries from either hunting or gathering. There was only one micronutrient deficiency that we were able to detect in these communities. While visiting the Trobriand Islands of Papua New Guinea we spoke to local anthropologists who explained to us that the albino trait we witnessed in a few of the children was due to a micronutrient deficiency, possibly due to low iron intake. It was our hypothesis that the limited diet in these far removed islands, which included only fish and fresh fruit, had caused this deficiency. However, it was the only deficiency disorder we had witnessed in any of these tribal communities. There had been no other physical or mental defects observed. One of the most amazing facts is that of the literal thousands of children we encountered not one from a remote tribe was overweight or obese. This continued to be the case for the adult males whose fit bodies looked decades younger than their actual ages. However, while the younger women were lean and fit, by the time they began baring children, about half of the women, although not overweight or obese by the American standard of BMI ratios, carried more fat on their well-muscled sturdy frames than the men. This would be expected to secure the success of childbearing and rearing, which lasted for many years of the adult female's life. Another interesting observation was that in the remote tribes we observed little or no tooth decay, and most often, their teeth were straight and white. Also, we noted that the tribes that ate protein and fats from hunting or fishing more frequently and in greater ratio to their agricultural based counterparts, were leaner and taller overall.

Our experiences with the remote tribes were eye opening and humbling. The amount of knowledge that these people shared with us about nature, food, herbal remedies, and survival went beyond anything we could have imagined. Prior to this expedition it would have been easy for us to imagine them as impoverished when we watched them on the Discovery Channel, or read about them in National Geographic. Make no mistake; these people do not live in poverty. That is because their lives do not yet revolve around money as you and I know it. Paper money or coin cannot build them a home, it cannot catch them food or buy them medicine. These people rely on every one of their tribe members for their expertise, in a variety of areas, in order to survive. Each does what is needed and is recognized for their actions. However, more frequently, paper money and coins are being brought in by foreigners and are being traded for their homemade wares. These remote tribal villagers then spend this newfound currency to buy something from a passing salesman or on an infrequent trip to a larger village. Often the newly acquired money is spent on the flashy processed foods that promise to replace their traditional, natural staples with better, newer and easier food options. Foods like margarine, white sugar, white flour, chips, candies, and sodas are the first to arrive. For these last remote tribes it is not the elements of nature or the harshness of their lives that will eventually bring them obesity, cancer, heart disease and diabetes; No, this they will buy in brightly colored packages with the paper and coin that we have given to them.